|

| Rotulistas |

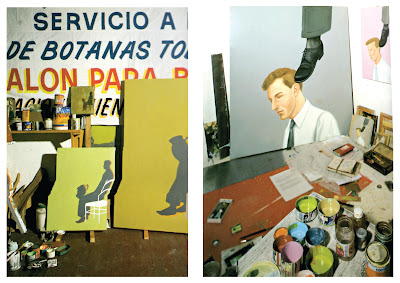

I first came across the work of Francis Alÿs in a book about Painting. The work featured was his Rotulistas series (1993-7). For this Alÿs used the tradition of signwriting (commonly used in Mexico, where Alÿs lives) to make comments on individuality, mechanical reproduction, how the mechanical has replaced the artisan, market forces, production value vs. use value, originality, intellectual copyright, authorship, collaboration, ethics, and exploitation. Alÿs produced a series of paintings based on the style of the painted adverts in his local neighbourhood. He then approached various signwriters to make enlarged copies. Once completed Alÿs made a new body of work based on the most significant elements of each sign-painter’s interpretation. The process was to contuse until the market could not absorb any more copies - that is until Alÿs couldn't sell any more. The project failed, in a sense, when Alÿs stopped it because he never reached that saturation point. To what extent was this exploitation? When you consider that he was employing tradesmen there seems to be no problem, until the question arises of how much they were paid compared to how much their paintings fetch. A decade after the project the paintings had amassed such value that they were well beyond the means of the humble signwriter – or even the artist himself. Of course this isn’t a problem unique to the art world – an advertising agency will undoubtedly made many times more as a result of an advertisement than they pay the commercial artist. “So what?” you might think, the artist agreed to work for that price, the ad-campaign might have been a failure, the company might have even lost money. True, but the bigger picture here is that of the worker and the CEO. How many times more should CEOs earn than they pay their workers? Think about it, you own a factory, you take the risk, it’s your factory, maybe you deserve a big part of the profit…but how much? Do you pay yourself twice as much as your average worker earns? Three times as much? Ten times? What would be reasonable? At what point would you be embarrassed, ashamed to look your workers in the eye? In 1965, CEO pay was 26 times that of their average worker. In 1980, [it was] 40 times. In 1989, it was 72 times. In 1999 it had risen to 310 times, and today [2001], as per the above data from the accounting firm, Towers Perrin, survey it has reached 500 times. Think about how much money that is! If a worker earns $20K then the CEO, in 1965, was earning over half a million dollars. By 2001 they would have earned £10million dollars while workers pay would have seen a negligible rise. Questions of ownership come into play and it becomes easy to take a Marxist reading of the Rotulistas series. If the workers become more productive and efficient (because of experience, for example) the owner’s profits increase, while the workers’ wages stagnate. In many countries workers can never aspire to own the good that they produce, every hour. The beauty about Alÿs’ project is that you can read all this into it, but you could just as easily focus on reproducibility and notions of authenticity. This also raises political questions. How can we trust news or media footage as both original (source) and authentic when digital media is so easily manipulated and replicated? The Rotulistas at least leave their own hand writing on their images, in this way each painting is unique, an original.

|

| Fabiola Installation shot |

Alÿs continues to explore themes of originality and exploitation in other works. The first exhibition of his that I saw was Fabiola at the National Portrait Gallery. For years Alÿs had collected paintings of Saint Fabiola. The original painting has long since been lost but people continue to make "copies" based on this original, as if there is some sort of cultural memory of the object. If enough of the hundreds of copies are similar, can we assume that the painting existed and that it looked like the copies? Seems reasonable, doesn't it? This raises questions about fables and religion, and Chinese whispers. Alÿs works with fables in many of his works.

|

| When Faith Moves Mountains |

Francis Alÿs, "When Faith Moves Mountains" (2002). from Daily Serving on Vimeo.

In his performance When Faith Moves Mountains he used hundreds of volunteer workers to literally move a mountain. The workers, armed with shovels and brooms moved the dirt and sand about 10cm. The mountain literally moved. Why did Alÿs do such a thing? Was it raise questions about workers rights and pay (as above)? He claims that it was to translate social tensions into narratives. Alÿs aimed to infiltrate the local history and mythology of Peruvian Society. He aimed to create a story that lived on beyond the act, a fable, or myth. Parallels to Hebrew slaves building pyramids or Stone Henge are evident.

In Barrenderos (2004) he performed a similar act. This time a line of street sweepers pushed garbage through the streets until they were stopped by the sheer mass of trash.

Alÿs is at his best when he refers to his environment - and this is done best in Mexico, where he lives. Through a kind of anthropological study of Latin-American people Alÿs is able to investigate resistance to modernisation. Mexico sits is a strange place, not quite 1st world, certainly not 3rd world. It has never fully integrated with the USA. Mexicans I met will tell you of their disdain for Americans but at the same time they will idolise US gangster rappers, they will buy US clothes, even have US posters in their house. Of course, they also go to the US to live and work as the salaries they can earn there as a waiter exceed what they can earn as a High School Principal in Mexico. Alÿs addresses such issues of resistance to modernity through his Ensayos (rehearsals). Two films provide

|

| Politics of Rehearsal |

good examples. In The Politics of Rehearsal (2004) a stripper undresses while a band rehearses. Every time the band stops, she starts to re-dress. This is a good metaphor for the flirtatious relationship Mexico has with the US. The stripper titillates us but we are never satisfied, as she never completes the routine. It is accompanied by a voiceover about the ideologies of the Modern in Latin America, which starts with Harry Truman’s inaugural address in which he coins the term “underdevelopment”. “One of the arguments of the work is that the notion of ‘development’ operates as a form of political pornography, transfixing us with a promise of arousal precisely because it is forever denied” (Cuauhtémoc Medina, Tate exhibition catalogue).

|

| The Rehearsal I |

In Rehearsal I (1999-2001) we see someone (presumably Alÿs) driving a Beetle car up a hill near Tijuana while we also listen to audio of a Mariachi band rehearsing. One can imagine this act in the context of Mexican migration to the US via Tijuana. Many of Alÿs’ works encapsulate epic struggle and failure (Paradox of Praxis I – sometimes doing something leads to nothing or The Loop (below), for example). Whenever the band stops so does Alÿs, and the car rolls backwards down the hill, of course, never reaching the top. I first saw these two films at the Francis Alÿs retrospective at the Tate in London. I usually find video art troublesome: you

|

| Patriotic Tales |

never know how long it will last (and it’s often very boring), why don’t they provide seats and timed screenings? Or if this is not possible, why isn’t video art shown on the Internet instead of the gallery? There are, however some exceptions where the art is engaging and you don’t care how long it is going to go on for (or that there is no seat). I found Alÿs’ Patriotic Tales to be one of these exceptions. I watched as Alÿs walked into the near empty Zocalo (main square in Mexico City famous for its giant Mexican Flag) followed by a line of sheep. Alÿs walks around the flagpole for some time in a mesmerising, entrancing act of repetition. The sheep follow, forming a circle. Eventually Alÿs slows down so that he becomes not the leader, but a follower at the back of the line. The sheep continue to walk in a circle, not knowing who they are following, unaware that in fact they are the leaders. This seemed, to me, to be a profound political statement about who we allow to lead our countries, and also how we have the power to become leaders – not just sheep that blindly follow. After a while the odd sheep walks off. Far from breaking the spell the majority of the sheep continue walking in a circle, even though they must have seen that they are free to leave – perhaps we can reflect on Crowd Theory and Safety in numbers here. The performance really is spellbinding and worth watching until its conclusion as one by one the sheep decide to leave.

Alÿs also makes more explicitly political works, three of which I will describe here:

- In The Loop Tijuana-San Diego (1997) he travelled from Tijuana to San Diego without crossing the US-Mexican boarder. In order to do so he travelled south through South America to Santiago de Chile, then via New Zealand and Australia to Singapore, Bangkok, Rangoon (hardly easy to get to in itself) Hang Kong, Shanghai, Seoul, Anchorage (Alaska) Vancouver before heading south to San Diego. The absurdity of such a journey reminds us how lucky we are to have freedom of travel and that others are not so fortunate. In fact, speaking about another project, Alÿs tackled the issue of freedom of movement directly by asking “…how can we live in a global economy and be refused free global flow?”

- “Sometimes doing something poetic can be political, and sometimes doing something political can be poetic” (Francis Alÿs – exhibition catalogue, David Zwirner Gallery, New York 2007). In 1995 Alÿs set out to make a poetic gesture about action painting for the São Paolo Biennale. He walked from the gallery carrying a leaking can of paint – which of course drew the line of his journey. For The Green Line (2004) Alÿs recreated this performance by retracing the portion of the green line (which denotes the demarcation line established after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War) that runs through Jerusalem. The resulting film features a voice over of the reactions of Palestinian, Israeli and International individuals.

- In 2006 Alÿs set out to create a bridge between Havana and Key West in Florida by lining up the boats of fishing communities in each city. The boats would never actually touch but would give the appearance of touching by their extension beyond the horizon. This work was a response to an article on the dispute between Cuban migrants and US Immigration. A law passed by Jimmy Carter states that if a Cuban is intercepted at sea they are to be returned to Cuba but if caught on dry land in the US they were to be granted legal right to remain in the country. In 2005, however, some of the Cuban migrants were intercepted on one of the bridges that link the Florida Keys – causing a debate as to whether they were allowed to remain or be returned. This performance was recreated in 2008, this time across the straight of Gibraltar using not boats, but children. Each child carried a boat made from a shoe and walked into the sea – half of them from the African side, heading towards Europe, and half from Europe heading towards Africa. Both formed a single-file line heading towards each other – obviously reminiscent of not just the 2006 Bridge but also The Loop.

|

| The Green Line |

|

| Don't Cross the Bridge before you get to the River |

|

| Bridge |

Alÿs’s approach is indeed poetic, and sometimes overtly playful. There is so much to his work that I cannot summarise it all here. There are multiple layers to his work, which can be read in different ways. Never didactic, he always seems to provoke debate. His works are “slow burners” that continue to engage and surprise me. He is, for me, the number one contemporary political artist.

A blog must be connected to the person in need. It is really important to understand the actual feel of such necessity and the essence of objective behind it. Author must give proper time to understand every topic before writing it.mexican painting art

ReplyDelete