A call to auction! –

CAN’T PAY YOUR FEES? WE’LL PAY YOUR FINES!

"There is this strange rite of passage that people seem to go through after they have had their education, they go on to vilify and hate students, as though the young are to blame for entropy and hair loss". (Jake Chapman, Evening Standard, March 2011)

In March 2011 the Chapman Brothers launched Can't Pay Your Fees? We'll Pay Your Fines - a call to auction! to support prosecuted student protestors. The same month they announced, in Dazed and Confused, more than 90 high profile signatories who have pledged to donate artwork or personal effects to the campaign. Here are just some of the signatories from page 1:

From the artworld:

Rachel Whiteread

Nigel Cooke

Gary Hume

Rebecca Warren

Ged Quinn

David Batchelor

(art dealer) Sadie Coles

(curator) Sir Norman Rosenthal

Jane Wilson

Liam Gillick

Francesca Gavin (Dazed and Confused)

Jenny Saville

Marc Quinn

and other celebrities:

Noel Fielding

Mick Jones (the Clash)

Stella McCartney

This is clearly a political act, and they are artists...but are they political artists? That is, do they make art politically? Is their artwork itself political?

| |

| Tragic Anatomies (detail) 1996 |

| ||||||||||||

| Zygotic acceleration, biogenetic, de-sublimated libidinal model (enlarged x 1000) 1995 |

|

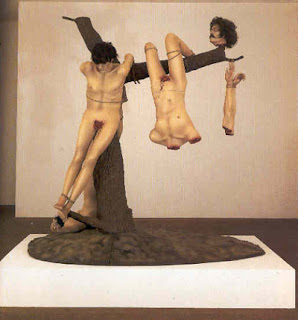

| Great deeds against the dead (1994) |

I was excited by Sensation. It seemed like new art, for my generation. Since then I've been surprised by the level of criticism leveled at some YBAs. Obviously if you want to be taken seriously in the artworld you need to slam Hirst and Emin (that seems to be a given) but where do the Chapmans fit in? They seem to be one rung up the ladder of acceptability (but only one rung). Perhaps they are easy to dismiss as enfants terribles, and that's the case with their defacement of Goya Prints. The Chapmans talk about the futility of their action here, as by defacing the artworks they actually increased their value. This is, of course not new. Piero Manzoni famously canned his own shit, which then accrued a value greater than its weight in gold. The Chapmans are at least self-aware in doing this. They talk about YBAs cynically, reminding us that the celebrity almost came before the work, and that anything made or belonging to the artist became valuable and collectable - just like a drawing by, say, Elvis would be valuable (whether or not it's any good). Gavin Turk's signature is another self-aware example building on the Manzoni precedent (one also thinks of Warhol, Klein, Duchamp... the list goes on). The act of defacing (a Goya print, or anything else) is inherently political. The fact that the Chapmans chose Goya's Disasters of War etchings is surely not entirely coincidental. We know they have been using them as source material long before they started defacing them (see Great deeds against the dead). Goya's print series was an extremely graphic and political protest against the Napoleonic atrocities committed in Spain (not entirely sure why he moved to Bordeaux to see out his last years, but we'll let that go). So we have a body of work that is a protest (Goya) which is defaced by the Chapmans, which is a form of resistance - I think. I think of it in the same vein as graffiti. Sure, some graffiti can be considered, and political, but most is not politically articulate. This doesn't mean it's not political though. The same can be said of the August rioters, much maligned for not banding together for political reasons but just "going down Footlocker and "tieving" shoes". The youths in questions (only 1 in 4 arrested were under 20 years old by the way, and rioters came from all walks of life including unemployed, employed, students, teachers, postmen...) were quickly branded as "criminals, pure and simple". The riots were seen by the right as opportunist. I'm not so sure. Just like graffiti, the riots were criminal (by definition) and they were not politically articulate, but they were a form of protest and resistance. People were exploding in frustration and saying "enough". Of course, it's sad that when law and order breaks down and people feel that can do what they want and get away with it, all they want to do is gather consumer goods - but that's symptomatic of a society where politicians make fake claims for second homes and plasma screen TVs, where the police sell details of dead children to the press and are complicit in phone hacking, where the press have no idea of when they cross the line, where the gutter press feed us celebrity rubbish and we lap it up. Since before Thatcher we've ushered in a particularly ferocious form of Capitalism called Neo-Liberalism where everything becomes about profit and everything is opened up to the market (national industries first, education more recently, and the NHS to follow). The Chapmans have criticised Tracey Emin, who Ed Vaizey has described as a Conservative supporter, for accepting a commission by Downing Street. Emin was also quoted (in the Sunday Times) criticising the 50% tax rate and considering leaving the country to go to France, where she has a holiday home. (You can read Emin's defense of those comments here and make up your own mind).

The Chapmans feel that too many of the YBAs aren't doing enough to oppose student tuition fees (Telegraph) but isn't this a bit hypocritical coming from artists whose career springboarded off the endorsement of Charles Saatchi - using money, in no small part made from Tory party advertising campaigns run by Saatchi and Saatchi in the 80s? OK, forget where the money came from, what about what Saatchi helped create? Are the Chapmans complicit with this? How about being represented by Jay Jopling - son of a Tory Baron? Does that not conflict with any political credentials? Can you be truly political and be in the pockets of such people, and make your money selling through the market? Maybe. I'm not against artists making money, especially if they are prepared to use it for political means (as in paying protestors' fines - although the Chapmans are hoping not to pay the fines directly from their own pockets but from the proceeds of an auction).

I went to the Frieze Art Fair last Sunday. I hated it. Hundreds of people are herded into a tent and shuffle around endless art, which you can't even look at because someone's either in the way or barges you out of the way in order to take a photograph. I only saw one or two pieces that I liked in the whole show but I couldn't even enjoy them because of Art Fair Fatigue. Knackered, the poor public, who have already been fleeced for the best part of £30 just to get in, head to one of the corporate style cafes to be fleeced even more. Be in no doubt, it's the art students and wannabe artists who keep this going. Their footfall means the fair can cover its costs regardless of any sales. In 2007 the Chapman brothers exhibited at Frieze. They made a protest against the money making market machine by defacing £10 and £20 banknotes, which they subsequently sold for... well, more than £10 and £20. The point is this, a drawing can be worth whatever the market is willing to pay - it's irrelevant how much the paper it's drawn on costs. No one really thinks that a drawing is worth more or less if it's drawn on Fabriano paper or on cheap, found paper. However, when you draw on a banknote you are confronted with its material value (it's written on the note in case you forget). This means you are unable to avoid the history of Piero Manzoni, Gavin Turk etc. The Chapmans' drawings are made quickly enough to be read as a signature. Of course, defacing the Queen's image is a crime and therefore the act of doing so is political. Defacing currency is political. The debate around value also becomes political. The Chapmans have one more political layer to this project though - a copyright issue. A graffiti artist, D*Face, has made remarkably similar images on banknotes since 2003 (see image above). The Chapmans claim to have never seen his work or heard of him and that defacing currency is as old as graffiti, which is as old as Lascaux cave paintings, so no one can lay claim to it. They claim that it's not original, and that's what interests them... it has no authorship. You can read a relatively neutral account in the Independent. D*Face claims that the Chapmans' claim to not know who his is is laughable. He says that he created a billboard sized version at the bottom of their road, read more here. The Chapmans' response is typically nihilistic. It reminds me of their frank explanation of the effectiveness of the Cant' Pay Your Fees? We'll Pay Your Fines project where they admit that they can't erase criminal records so having your fines paid is only the tip of the iceberg and that the protestors will inevitably face financial penalties over their careers as a result of the stigma. If their position on market forces is ambiguous so is their position on originality. But their position on tuition fees is very clear. They may feel that they can't change government policy, they may not have an alternate solution, but they definitely oppose tuition fees. This article in the Evening Standard sums them up pretty well, "Jake and Dinos Chapman have carved a niche for provocative ambiguity...the brothers have delighted in prompting awkward moral dilemmas for the viewer, and provoked endless speculation about their own views on society". No one likes being lectured, so an ambiguous position is always intriguing. It allows us to question our position as we question theirs. Hence, regardless of any hypocrisy, I think their work functions well as contemporary political art. It confronts us and challenges us and in doing so allows us to consider our position and what we might want changed in our ideal world.

I went to the Frieze Art Fair last Sunday. I hated it. Hundreds of people are herded into a tent and shuffle around endless art, which you can't even look at because someone's either in the way or barges you out of the way in order to take a photograph. I only saw one or two pieces that I liked in the whole show but I couldn't even enjoy them because of Art Fair Fatigue. Knackered, the poor public, who have already been fleeced for the best part of £30 just to get in, head to one of the corporate style cafes to be fleeced even more. Be in no doubt, it's the art students and wannabe artists who keep this going. Their footfall means the fair can cover its costs regardless of any sales. In 2007 the Chapman brothers exhibited at Frieze. They made a protest against the money making market machine by defacing £10 and £20 banknotes, which they subsequently sold for... well, more than £10 and £20. The point is this, a drawing can be worth whatever the market is willing to pay - it's irrelevant how much the paper it's drawn on costs. No one really thinks that a drawing is worth more or less if it's drawn on Fabriano paper or on cheap, found paper. However, when you draw on a banknote you are confronted with its material value (it's written on the note in case you forget). This means you are unable to avoid the history of Piero Manzoni, Gavin Turk etc. The Chapmans' drawings are made quickly enough to be read as a signature. Of course, defacing the Queen's image is a crime and therefore the act of doing so is political. Defacing currency is political. The debate around value also becomes political. The Chapmans have one more political layer to this project though - a copyright issue. A graffiti artist, D*Face, has made remarkably similar images on banknotes since 2003 (see image above). The Chapmans claim to have never seen his work or heard of him and that defacing currency is as old as graffiti, which is as old as Lascaux cave paintings, so no one can lay claim to it. They claim that it's not original, and that's what interests them... it has no authorship. You can read a relatively neutral account in the Independent. D*Face claims that the Chapmans' claim to not know who his is is laughable. He says that he created a billboard sized version at the bottom of their road, read more here. The Chapmans' response is typically nihilistic. It reminds me of their frank explanation of the effectiveness of the Cant' Pay Your Fees? We'll Pay Your Fines project where they admit that they can't erase criminal records so having your fines paid is only the tip of the iceberg and that the protestors will inevitably face financial penalties over their careers as a result of the stigma. If their position on market forces is ambiguous so is their position on originality. But their position on tuition fees is very clear. They may feel that they can't change government policy, they may not have an alternate solution, but they definitely oppose tuition fees. This article in the Evening Standard sums them up pretty well, "Jake and Dinos Chapman have carved a niche for provocative ambiguity...the brothers have delighted in prompting awkward moral dilemmas for the viewer, and provoked endless speculation about their own views on society". No one likes being lectured, so an ambiguous position is always intriguing. It allows us to question our position as we question theirs. Hence, regardless of any hypocrisy, I think their work functions well as contemporary political art. It confronts us and challenges us and in doing so allows us to consider our position and what we might want changed in our ideal world. |

| If Hitler had been a Hippy How Happy Would We Be? |

"Dinos Chapman said the work, entitled If Hitler had been a Hippy How Happy Would We Be, was a rumination of what might have been had Hitler not been refused entry to Vienna's art school. He added they showed a "blankness" rather than any hint of the deadly pathology that he would later demonstrate". (Independent)Of course, Nazis feature heavily in the Chapmans' work. In works such as Hell the Chapmans showed us apocalyptic and dystopic visions of a world not too far away from ours, referencing Auschwitz and McDonalds. Part of their vision of dystopia is the power of capital (as seen through their defacing of banknotes or opposition to tuition fees). Part of the dystopic nature of the power of capital is corporate and consumer greed (as referenced through mannequins and trainers). The Chapmans don't aim, or claim, to give us any solutions to our contemporary malaise, and they don't. But they do confront us with the causes in confusing and ambiguous ways, in the same way that punk replaced political action with a defiant nihilism and transformed apathy and pessimism into a weapon of resistance.